Cineworld 📽️ is FOOKED 🍿

Or why the world's second-largest cinema chain will likely struggle to pivot out of a structural rabbit hole

Happy Monday, everyone.

Except for Cineworld shareholders, employees, and fans. They woke up to the news of the world's second-largest cinema chain closing all of its UK and US cinemas this week until further notice. We're talking 787 cinemas and around 45,000 employees affected. This year's often-repeated meme is that COVID-19 became the "Chief Digital Transformation Officer" for many businesses, and incumbents have no other choice than to change (or, well, die). But is a radical pivot even possible for Cineworld, given its business model? And if it is - then what are the options?

Cineworld pre-COVID

Cineworld's history goes back to a cinema theater in Haifa, Israel, started by Greidinger family in 1930. Exactly 90 years later, it was the world's second-largest cinema chain, with 2019 revenues at $4.4bn, ran by the grandsons of the founder - Mooky Greidinger, the company's CEO, and Israeli Greidinger, his deputy.

The brothers started their aggressive growth strategy by expanding the company (then called Cinema City) from Israel into Eastern Europe in the late 1990ies. In 2014, they acquired UK's second-largest chain, Cineworld, for ca. $825m (£503m) and merged the two companies under Cineworld's brand name. In 2018, Cineworld bought a US-based chain, Regal Cinemas, for $3.6bn. A couple of months ago, the company was on track to becoming the largest cinema operator under a $2.3bn deal to acquire the Canadian cinema company Cineplex. Not bad for what used to be this little cinema building only a couple of generations ago, right?

Source: Pinterest

We all can guess what happened next

Yes - COVID-19. It brought streams of bad news one after another. Just like blockbusters were bringing streams of customers into Cineworld's movie theaters in what now seems a very distant past.

Global City Theaters, the family trust of Greidinger family, had to sell a 7.9% stake in the business for $150m in early March. As cinemas in the US and the UK started closing in March-April, Cineworld agreed on the terms of an additional $110m revolving credit facility, secured further $45m through the UK's CLBILS loan scheme and applied for $25m through the US government CARES Act.

In June, Cineworld backed out of the mega-deal with Cineplex citing "a material adverse effect." Toronto-based Cineplex started litigation over a failed deal soon after.

While cinemas partially reopened in summer, Cineworld's interim results for the 6 month period ended June 30th, 2020, painted a bleak picture. Revenues down 67% from $2.2bn for the same period in 2019, to $712m. A total $1.6bn pre-tax loss. And all this while the company's net debt (incl. leases) as of June 30th was a staggering $8.2bn, which even pre-pandemic was at ca. 5x EBITDA.

The announced pushback of James Bond's newest saga, "No time to die," into 2021, was the final straw that might just break Cineworld's back. Studios already delayed many Hollywood blockbusters into 2021, and "No time to die" was the last big hope of cinema chains. However, MGM wasn't exactly inspired by Warner Bros' Tenet (latest Cristopher Nolan's movie) lackluster performance in the US market and pulled the plug on Bond. Given chains like Cineworld make most of their money from top movie hits - company execs realized they have nothing to bank on for the next 2-3 months and decided to cut their losses for now.

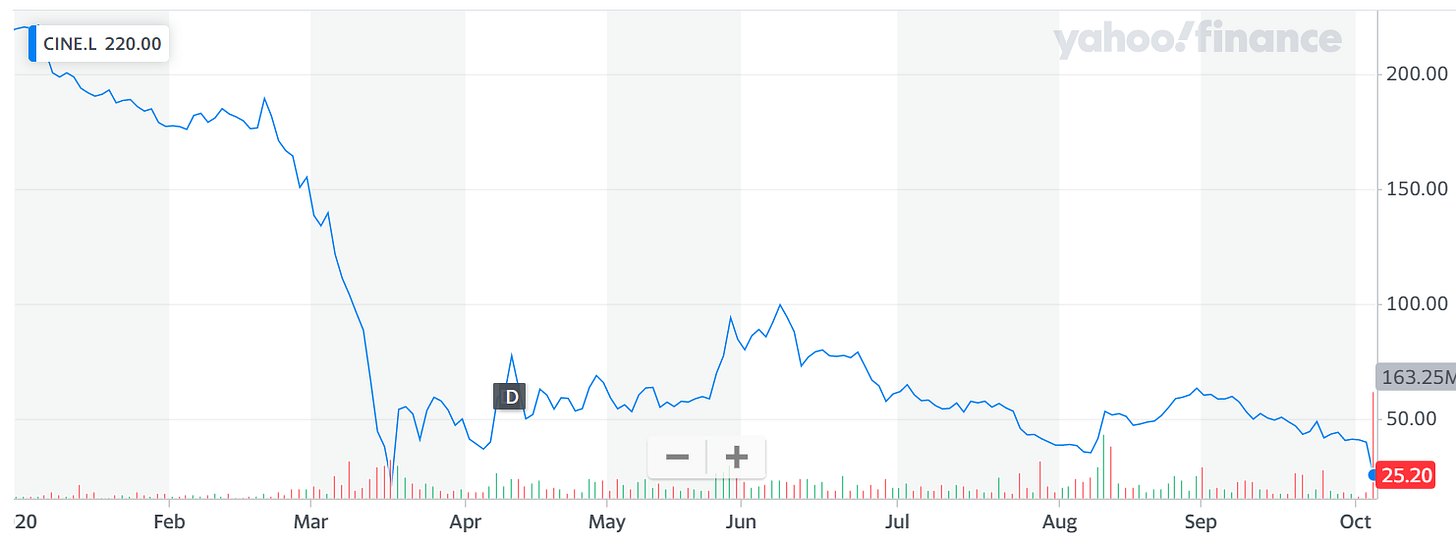

Cineworld's stock price says it all. 40% down upon today's announcement, and worth only 1/10 of what it was when the year started.

Source: Yahoo Finance

I will leave the debate about whether Cineworld can restructure its debt, renegotiate covenants and leases, fire-sell some assets, etc. to the bankruptcy gurus at Petition (a shoutout these guys don't even need).

Cineworld might well be able to pull this restructuring off. But financial engineering is not the focus of this post - I am more interested in exploring what Cineworld can do with its core business. Which is, as of now, operating cinemas.

To do that - I need to understand Cineworld's business model first. Thankfully, it is not complicated. I used the company's 2019 annual report for this analysis.

How does Cineworld earn its money?

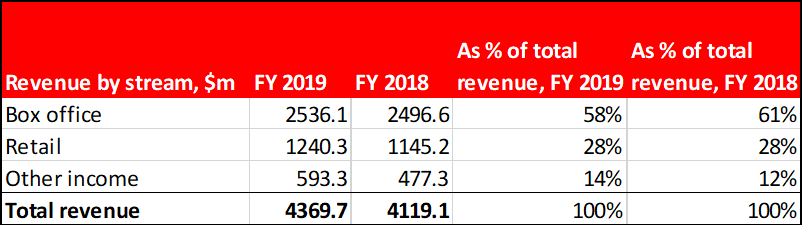

Cineworld has three primary revenue streams:

Box office (ticket sales)

Retail (food and drinks sold in the cinemas)

Other income (primarily revenue from selling on-screen advertisement and commission on online ticket bookings)

Here's how these revenue streams looked like as % of overall revenue in 2019 and 2018:

One thing you should see straightaway is all three revenue streams are 100% contingent on customers physically coming into the theaters. And that's the first problem - when cinemas are closed, there isn't much you can do.

If/when customers are back - you can tinker around with ticket 🎟️ prices, ticket commissions, and prices for food 🌭 🍿 and drinks 🥤. Although - good luck with that, when AMC had to offer $0.15 tickets to lure customers back into their movie theaters in August.

But they are still open outside the US and UK, right?

Yes, that's correct. Cineworld operates cinemas in mainland Europe - Poland, Romania, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Bulgaria, Slovakia, and Israel. In many of these countries, lockdown measures are not as strict as in the US or UK, and most of Cineworld's cinemas (except for in Israel) are still open.

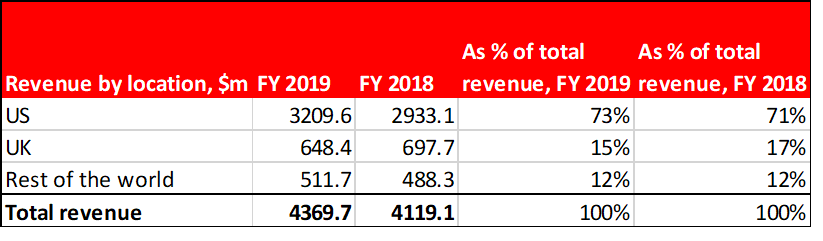

However, here's the second problem - all these represent a not-so-impressive 12% of Cineworld's total revenues, as you can see below:

The adjusted EBITDA margin of 27.4% for "Rest of the world" was better than in the US (23.6%) or UK (18%) - which is good news. However, the point still stands - you can optimize the hell out of those markets, but it won't change the overall picture much. Cineworld might generate cash by selling its operations outside of the US or UK - however, finding a buyer at anything other than a distress price in this climate would be a miracle.

P for Pivot

Oh, the sweet hopes of digital optimists (myself included). COVID-19 is not just a shock - it is also an opportunity, right?

How about hiring a Chief Transformation Officer, engaging McKinsey or BCG, shutting execs down in a war room for a couple of weeks, so that they can crawl out of it with a glossy 150-page "roadmap"? Surely, Cineworld can "reimagine customer experience in digital channels," "construct a digital-proof organization," "harness the power of AI, robotics, big data," and "automate business processes"? And we can all live happily ever after?

Sorry for the sarcasm (not sorry). The third (and biggest) problem of Cineworld is they own NOTHING that can be digitized.

The main draw attracting customers to cinemas (except for caramel popcorn 🍿 and nachos with extra cheese 🧀) are movies, i.e., content. And Cineworld doesn't own content - movie studios do.

Historically, cinemas enjoyed a 90-day "theatrical window" during which movies were available to them exclusively, before hitting streaming services or Video-On-Demand. That's when Cineworld and its competitors made money. Since the pandemic hit - studios are squeezing cinema chains on multiple fronts:

Studios are cutting "theatrical windows" down to as short as 17 days.

Even when cinemas reopen and Cineworld manages to lure customers in - they will have a lot less exclusive time to make money. Pre-pandemic, people didn't want to wait for three months to watch their favorite movie. But how many would be willing to risk their health (and eat popcorn with a mask half on), if you only need to wait for 2-3 weeks tops?

Studios are going directly to consumers, bypassing theaters altogether - just like Disney did with "Mulan." And studios which don't have their own subscription service will be a lot more susceptible to "cutting out the middleman," aka Cineworld and going to Netflix or Amazon Prime directly.

Yes, you might have read in your local news that some theaters are offering curbside pickup or delivery of popcorn in an attempt to pivot. Pardon my pessimism - but these are pre-death seizures. Like the ones many restaurants and coffee shops in the now empty, ghost-like Wall Street or the City of London had before they eventually gave up on the fight.

In the sad value chain of 2020, Cineworld is a dry pipe (empty theater room) for distributing content (movies), which fights a losing battle against the always roaring pipes of Netflix, Disney+, and Amazon Prime. And these don't depend on government COVID protocols and customers' health concerns.

Is that really it?

I won't go as far as saying that the movie theater industry, and movie theater companies with it, are dead. At the end of the day, we attend movie theaters for the experience. Like my experience of watching "Gone in 60 seconds" on my own in the Soviet-style movie theater back in 2000, because the high school cutie who I invited didn't show up (true story 😢).

Elegant independent cinemas like this beauty in Portobello Road, London will still be in demand (by the way, Cineworld owns 26 arthouse cinemas under the Picturehouse Cinemas brand in the UK). Watching a movie on a rooftop with a glass of prosecco, or in a public park when picnicking with friends is also an experience we won't get in our living rooms.

Source: TimeOut

But the long-term strategic prospects of a predominantly mainstream cinema chain, like Cineworld, are bleak. Pivoting out of a structural rabbit hole is going to be very, very hard, given the three problems I explored above:

Cineworld's business model is entirely reliant on customers physically attending movie theaters.

The company can't rely on geographical diversification, as its revenues outside of the US and the UK are immaterial.

It is a dried out pipe for someone else's content, surrounded by a network of other, fully active, pipes.

Or, as Conor McGregor would say - Cineworld is FOOKED.

Source: Memegenerator.net

I hope you enjoyed this post - subscribe to get your weekly dose delivered straight into your inbox.

Also, I am keen to hear your feedback. It's easiest to catch me on Twitter - let's connect! I cover topics at the intersection of digital transformation, effective communication, and burning business headlines every week.

Until next time,

Dmytro